At a time when the effects of climate change are accelerating and published science overwhelmingly supports the view that humans are responsible, powerful groups remain in denial in key sectors such as politics and the media.

So now, more than ever, we need scientists and policymakers to work together to create and implement effective policy which is informed by the most recent and reliable climate evidence.

We know that trust between scientists and policymakers is important in this regard, but how do you build this trust, and how do you make sure that it genuinely leads to positive outcomes for society?

In a new study published in the prestigious journal Nature Climate Change, Dr Christopher Cvitanovic from the University of Tasmania's Centre for Marine Socioecology has co-authored research into the issue of trust between climate scientists and policy makers.

The research, led by the CSIRO’s Dr Justine Lacey and also involving researchers from the Climate Change Institute at the Australian National University, shows that in cases when you have "too much" trust between scientists and policy makers, the benefits of trust can instead manifest as perverse and unwanted outcomes.

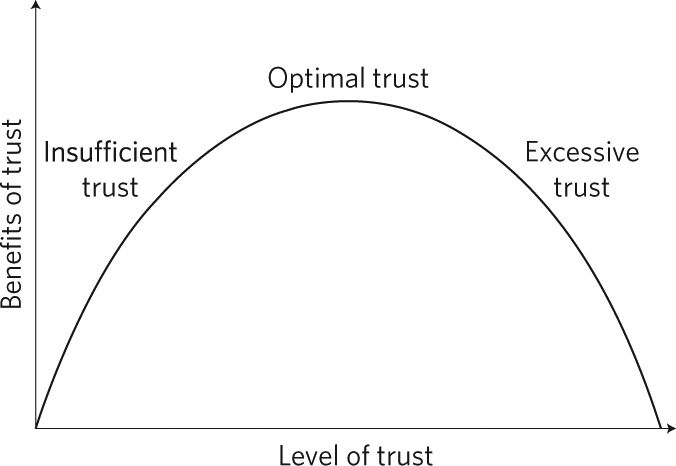

“While trust between scientists and policy makers is a necessary precondition for evidence-informed decision-making, too much trust can be as much of a problem as too little trust,” Dr Cvitanovic said.

“For example, excessive trust can lead to “blind faith” commitments between policy-makers and scientists, whereby a policymaker trusts an individual scientist so much that they do not look for signs of misconduct, such as the misrepresentation of findings.

"It could also lead to "Cognitive lock-in", whereby a policymaker sticks to a failing policy because they feel committed to the scientist who first recommended the course of action; or “Capture”, whereby a scientist may promote only their own stream of research to the policymakers, narrowing the scope of what science enters the policy arena. .

“For this reason previous research in this area has identified the need for the ‘optimal amount’ of trust, which benefits both scientists and policy-makers while minimising the risks.”

Dr Cvitanovic said the study builds on previous research, by identifying five key insights for how to better manage trust at the interface of climate science and policy, and the risks associated with it:

“Research such as this is just the beginning of a discussion about navigating trust between climate scientists and policy-makers.

“By ensuring that we have the optimal amount of trust between these two groups, we can minimise the risks while ensuring that both they and the broader community benefit from the insights that climate science is providing,” Dr Cvitanovic said.