The chance discovery of a unique set of whaling records dating back to 1952 has provided new insights into the lives and physiology of humpback and sperm whales.

IMAS PhD student Lyn Irvine heard from a retired whaler about the records, which detail the activities of the Cheynes Beach Whaling Station in Western Australia between 1952 and 1978, and tracked down the hand-written originals in WA’s State Records Office.

Unusually, the thousands of pages of records list the amount of oil recovered from individual whales, whereas other stations around the world aggregated data for batches of whales on a weekly or annual basis.

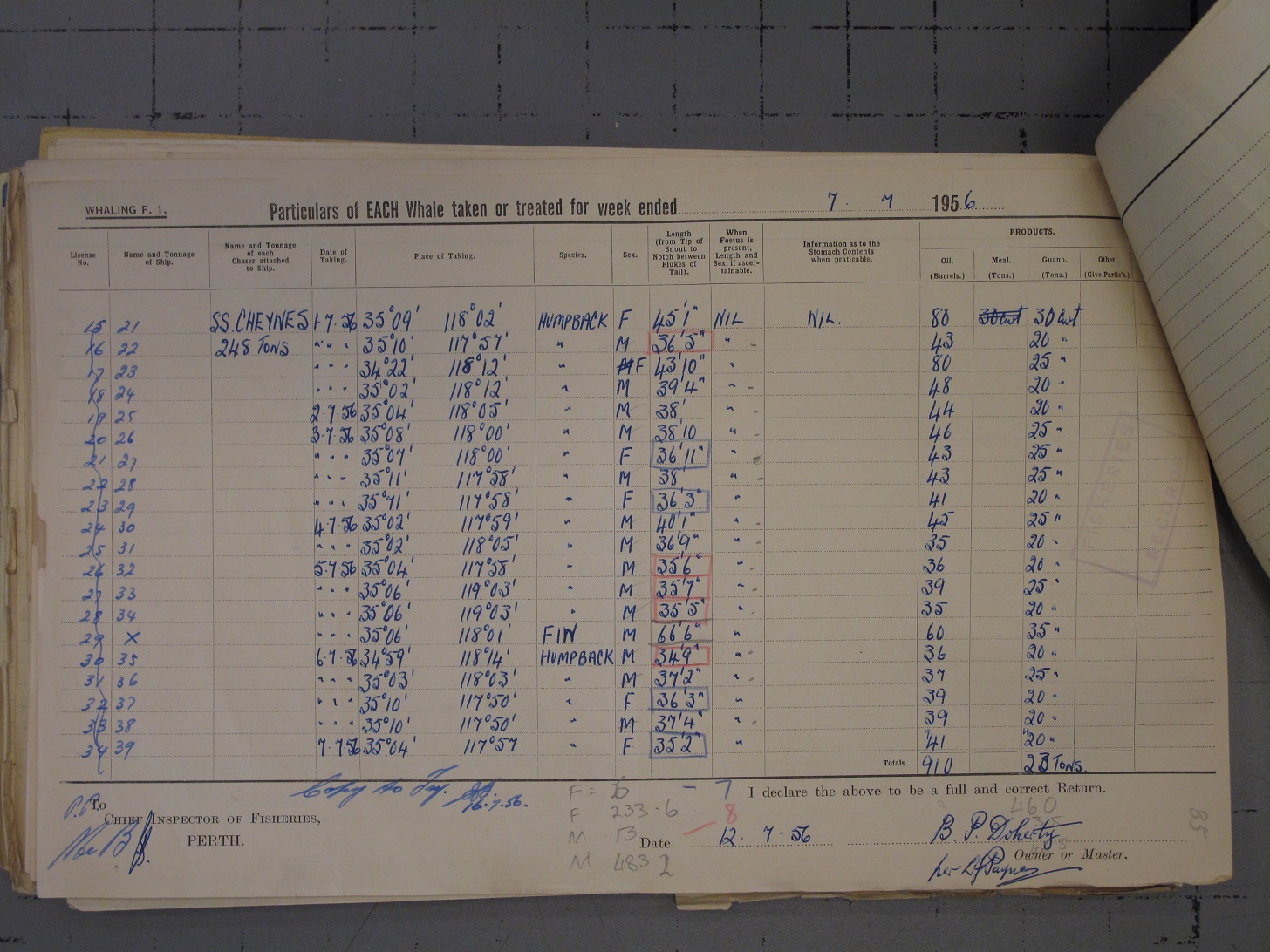

The records (Pictured, left, a 1956 record from Cheynes Beach whaling station) allowed Ms Irvine and an IMAS-led research team to analyse how humpback and sperm whales store oil and utilise it as energy during different life stages, with the results published in the international journal Royal Society Open Science.

The records (Pictured, left, a 1956 record from Cheynes Beach whaling station) allowed Ms Irvine and an IMAS-led research team to analyse how humpback and sperm whales store oil and utilise it as energy during different life stages, with the results published in the international journal Royal Society Open Science.

“It’s ironic that records from an industry which pushed whales close to extinction are now informing research that could contribute to their long-term survival,” Ms Irvine said.

“Previously, it was known that the amount of energy whales stored as lipid (oil) varied according to their life history, reproductive status and the time of year.

“But the opportunity to quantify these relationships is rare, which is what makes these records, collected as oil that was extracted from every part of the whale carcass, so important and unique.”

Ms Irvine (Pictured, right) said analysis of the amount of oil extracted from whales at Cheynes Beach reveals how much energy individuals store, for key events such as pregnancy and migration.

Ms Irvine (Pictured, right) said analysis of the amount of oil extracted from whales at Cheynes Beach reveals how much energy individuals store, for key events such as pregnancy and migration.

“Humpback whales store more total body lipid than sperm whales because humpbacks need to fuel their annual migration.

“Pregnant humpback whales store more energy than both non-pregnant females and males.

“Sperm whales don’t migrate and therefore maintain a constant level of lipid storage year-round.

“Analysis of lipid storage also shows that some pregnant female humpback whales delay their departure from their Antarctic feeding grounds to maximise their energy stores to satisfy the high costs of gestation and lactation.

“Smaller pregnant females, however, do not accumulate as much energy as larger females and are therefore more vulnerable to nutritional stress during migration.

“This research has provided new insights into the life history strategies of large whales, and its findings will help us to better understand the potential impacts on whales of environmental change.

“Now that whaling has ended, such a large and detailed dataset on cetacean energy stores will likely never be collected again,” Ms Irvine said.

The research is available here.