Climate modellers have a precious skill: they can create scenarios of past and future worlds for use by science, environmental and resource managers.

The problem, according to one of Australia's leading ocean modellers CSIRO's Dr Trevor McDougall, is there are not enough modellers to go around – in Australia or overseas.

"Research institutions should be prepared for a talent war as demand for modelling skills outstrips availability," Dr McDougall says.

Like many senior Australian climate scientists, Dr McDougall has PhD students within the joint CSIRO-University of Tasmania Quantitative Marine Science Program (QMS) – the first CSIRO PhD program in Hobart focussed on training marine science and climate modellers.

A total of 28 students from seven countries are presently enrolled in the Program, which will take in another seven students in 2010. Subject areas include: Marine Environment Prediction, Climate Variability and Resource Management, Climate and Ecosystems, Environmental Conservation and Management.

Dr McDougall says international demand for ocean modelling research in climate science has increased substantially due to government recognition of the value of understanding the ocean environment and oceanic influences.

"Such demand is contributing to the worldwide skills shortage, particularly in climate sciences, and the intent of establishing the QMS program is to reshape capabilities so that Australia can retain, nurture, and grow our quantitative expertise."

He says Australia's major research organisations are continuing to invest in model development.

"Just last month a CSIRO model was one of two that provided the basis for the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation to map future food production based on a range of climate scenarios."

Other major users of model output range from all tiers of government with responsibility for environmental management to international aid projects and the primary international climate reporting body, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

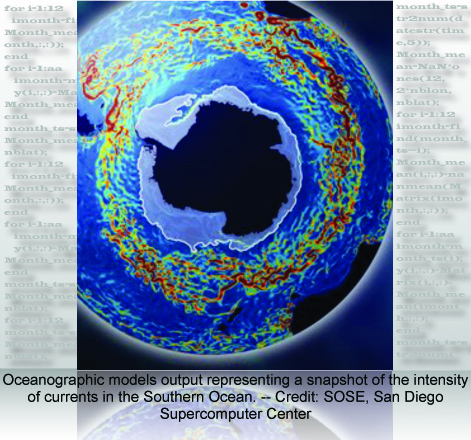

"In researching the complexities of ocean physics, physical oceanographers use mathematical equations to explain the movement and profile of the world's ocean currents," Dr McDougall says. "They enter those equations into models and the data downloaded from a range of sensors on ocean-going platforms such as drifting and moored buoys, ships and satellites, are then used to start and then validate, or invalidate, the models' results.

"These models produce a guide to how phenomena - such as sea level and ocean temperature variations - may evolve," Dr McDougall says.