Scientists have warned that vital ecosystems around Australia and Antarctica are collapsing, and propose a three-step framework to combat the irreversible damage that will impact the natural world and ultimately our survival.

The report, published in the international journal Global Change Biology was authored by 38 eminent scientists from universities and government agencies in Australia, the UK and the US.

Lead author, Dr Dana Bergstrom from the Australian Antarctic Division, said that the project emerged from a 2018 conference inspired by her ecological research in polar environments.

“I was seeing unbelievably rapid, widespread dieback in the alpine tundra of World Heritage-listed Macquarie Island and started wondering if this was happening elsewhere,” Dr Bergstrom said.

“With my colleagues from the Australian Antarctic Division and the University of Queensland, we organised a national conference and workshop on Ecological Surprises and Rapid Collapse of Ecosystems in a Changing World, with support from the Australian Academy of Sciences.”

The resulting report and extensive case studies examine the current state and recent trajectories of 19 marine and terrestrial ecosystems across all Australian states, spanning 58° of latitude from coral reefs to Antarctica. The case studies showed that:

The ecosystems studied included the Great Barrier Reef, mangroves in the Gulf of Carpentaria, the arid zone of central Australia, Shark Bay seagrass beds in Western Australia, Gondwanan conifer forests of Tasmania, Mountain Ash forest in Victoria, moss beds of East Antarctica, and the Great Southern Reef kelp forests.

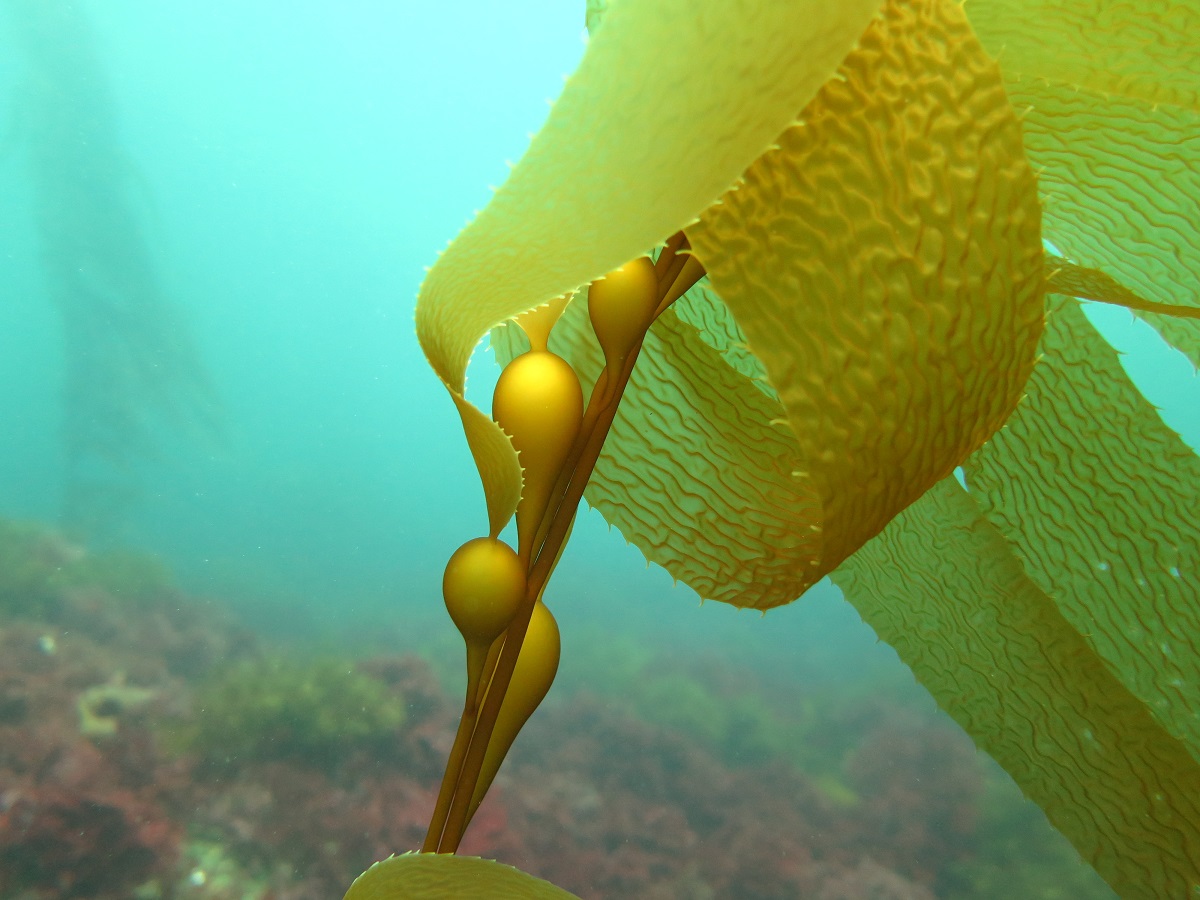

Giant kelp forests in decline

IMAS researcher and co-author, Professor Craig Johnson, said Tasmania had not been spared from ecosystem collapse.

“In Eastern Tasmania, we have experienced massive loss of giant kelp forests in response to ocean warming, and extensive destruction of other kelps and seaweeds from overgrazing by invasive sea urchins.

“But loss of highly productive kelps is not unique to Tasmania, with extensive losses in other states occurring for a variety of reasons,” Professor Johnson said.

“In Western Australia, heatwaves and southward movement of subtropical grazing fish has seen extensive kelp loss, while off Adelaide in South Australia, kelp loss is associated with decline in water quality, and in Victoria’s Port Phillip Bay overgrazing by urchins and water quality issues have been the culprits.

“In Western Australia, heatwaves and southward movement of subtropical grazing fish has seen extensive kelp loss, while off Adelaide in South Australia, kelp loss is associated with decline in water quality, and in Victoria’s Port Phillip Bay overgrazing by urchins and water quality issues have been the culprits.

“Urchin overgrazing has also caused kelp losses on the eastern seaboard in Victoria and NSW, although the southward range extension of subtropical fish grazers has also been problematic on some offshore islands,” he said.

Anticipating change, taking action

The report recommends a new 3As framework to guide decision-making about actions to combat irreversible damage.

“This includes awareness, anticipation and action – awareness of the importance of the ecosystem and the need for its protection, anticipation of the risks from current and future pressures, and action on reducing the pressures to avoid or lessen their impacts,” Professor Johnson said.

“While local action will not affect ocean climate change, a variety of local management responses can assist to mitigate risk of kelp collapse from climate change.”

The report determined that even apparently resilient ecosystems are likely to suffer collapse in the near future, as the intensity and frequency of pressures increase.

"Anticipating and preparing for future change is necessary for most ecosystems, unless we are willing to accept a high risk of loss,” Dr Bergstrom said.

“While the environmental change we see can be disturbing, I’m pleased to be part of a team sharing information that can guide decision-making to future-proof the ecological wealth that underpins our society.”

Images:

Published 26 February 2021